The Divine Comedy opens with darkness. As Professor Claudio Giunta writes in her latest book Inferno (pubd. by Feltrinelli, 2023), «today, the idea of a “dark forest” no longer scares us, but a fourteenth-century reader had a very clear perception of how frightening it could be to find yourself alone in a forest, at night, in the dark.» But darkness is not only actual darkness; it has other specific meanings too. This is clearly demonstrated by the photographic works of Carlotta Valente, created together with Joaquín Paredes, featured in the Dante’s gaze – the mimetic observer exhibition on show at Palazzo Barberini in Rome until 29th February. This range of images featuring plants, stars and animal negatives interpret the different types of light described in the Divine Comedy. In the exhibition promoted by the Central Institute for Ministry of Culture Cataloguing and Documentation, curated by Alessandro Coco and Peter Lang and coordinated by Giorgio Di Noto, we perceive in the most immediate way possible – i.e. through sight – the variations of light that appear throughout Dante's great poem, right up to the point when the poet crosses Purgatory and reaches Paradise, where his adored Beatrice resides.

Inferno (Hell), in fact, begins in darkness, as we follow Dante and Virgil into the shadowy bowels of the Earth with only the light of Virgil's lantern indicating the path and illuminating the damned and their suffering. «I came into a place mute of all light,» says Dante at a certain point in Canto V.

In Purgatorio (Purgatory) the poet sees a glow that in the next cantica, Paradiso (Paradise) will become a blinding light. In Paradise, Dante’s final destination, the souls of the blessed dead appear as flames, like lights. They have a slightly immaterial quality as they have lost the sharpness that distinguished the souls of the damned and those waiting to ascend to the Creator, and have therefore become a source of light in themselves. In the last Canto Dante writes: «O Supreme Light, who lifts so far above mortal thought, lend to my mind again a little of what you seemed then». As the critic Giulio Ferroni says, «Dante helps us understand the otherness of sight» and he does this by continuously using the metaphor of light.

Light and its various properties are one of the leitmotifs that run throughout the Divine Comedy, as shown by the photographs in the Dante’s gaze exhibition. The climax of Dante's journey, which stretches from the darkness of Hell to the ultimate divine splendour of Paradise, is rendered by Carlotta Valente and Joaquín Paredes not only through their subjects but more specifically by the characteristics of the photographic medium itself, which is particularly dependent on light. As Carlotta Valente explains, «the 27 works in the exhibition use light and the transmission of or resistance to light of the materials that were chosen to create them.» This takes us on a journey not only into the Divine Comedy but also through a series of historical photographic processes

To create the works dedicated to Hell, Valente uses paper due to its opacity and resistance to light. She also adopts the solarization technique, or more specifically the Sabatier effect: a process that involves switching on the light in the darkroom to "singe" the lighter print tones.

Carlotta Valente - Hell: Wolf

To represent Purgatory, on the other hand, Valente uses glass to create her photographs, as it is transparent and casts a shadow, just like the souls in this cantica. As she explains, cyanotype printing was chosen as a tribute to Anna Atkins (the botanist and first woman to use cyanotype printing to make a book) and also because blue is the first colour seen by Dante after the darkness of hell.

Carlotta Valente - Purgatory: Pine

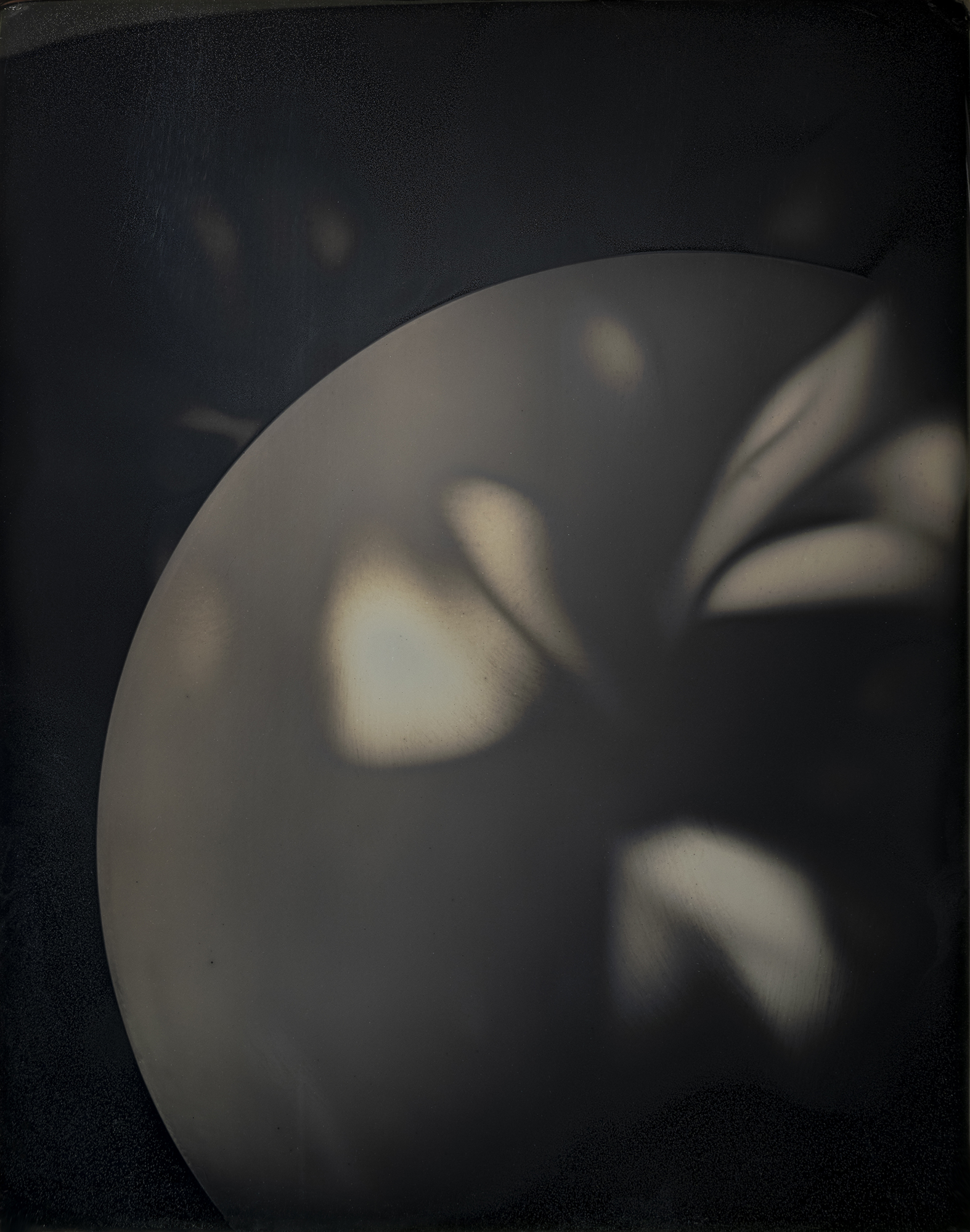

The technique used to create the photographs for Paradise is the most precious and the first historical photographic process: the daguerreotype. This involves creating a silver surface that is sensitive to light, so the image is imprinted on the plate but remains extremely difficult to see. «One of the reasons we chose this material to represent the last cantica of the Divine Comedy, is that it creates images that are difficult to see. This is because when Dante arrives in Paradise, he is totally blinded and cannot see anything at all,» explains Valente.

Carlotta Valente & Joaquín Paredes - Paradise: Planet

The exhibition at Palazzo Barberini therefore shows us how one of the literary works that has shaped Western civilization can also be interpreted as a lengthy quest for light.